Russification in Occupied Ukraine

“Living there, it seems like you live your normal life. But you can’t express your thoughts, there are topics you can’t discuss, you can’t go where you want. You live like a spider in a jar. You are kept inside, and you run in circles like horses in a circus ring. Those who expect Ukraine to save us are having a hard time. It’s hard on morale. You’re not allowed to speak about Ukraine; Ukrainian symbols are banned. If you hear something, or say something they think is wrong, they grab you and put you in a basement."

As many as 11 million people could be living under Russian occupation in Ukraine, according to UN and Russian figures, although it is impossible to know how many of them have already left. That’s the estimate of the population of the four Russian-occupied regions of Ukraine illegally annexed by Moscow in September 2022: Donetsk, Luhansk, Kherson and Zaporizhzhia, which together with Crimea amount to almost 20% of the internationally-recognised territory of Ukraine, a swath of land bigger than Hungary or Portugal.

Trapped between frontline fighting and the borders of Russia proper, residents of these regions navigate a reality where torture, death, coercion, deportation, cultural assimilation and military indoctrination are rampant, according to eyewitness and expert accounts, potentially contravening international law and in some cases amounting to possible war crimes.

The mostly Ukrainian-born population live all but cut off from the world. With Russian authorities controlling the access given to international observers and bona fide news organisations, these areas have become an information black hole on the European continent. A team of journalists from several European public service media, under the umbrella of the EBU Investigative Journalism Network, have spent months collecting reports from the ground and expert testimonies, analysing official communications from Russian authorities and first-hand descriptions of life under occupation. Repeated requests for an interview were made via a Russian embassy in the past few weeks; they went unanswered.

Statements and evidence gathered indicate a system is already in place where basic services are contingent on accepting Moscow rule. Access to food, education, jobs, health-care and life-saving medicines, as well as pensions or property, require swearing allegiance to Russia and its constitution and in some cases publicly renouncing Ukrainian citizenship, all to obtain a Russian passport.

“There is one very important consequence of this imposed Russian citizenship”, says Kateryna Rashevska, legal advisor at the Regional Center for Human Rights in Kyiv. “These people are now forced to serve in the Russian armed forces, and that’s why this is a war crime.” According to a report by the Russian Ministry of Defence, of the 300,000 men mobilised in the fall of 2022 to fight the “special military operation” in Ukraine, 80.000 were from the Donetsk and Luhansk regions; internally displaced people who have recently left Kherson and Zaporizhzhia report that recruitment offices there are starting to summon men of military age.

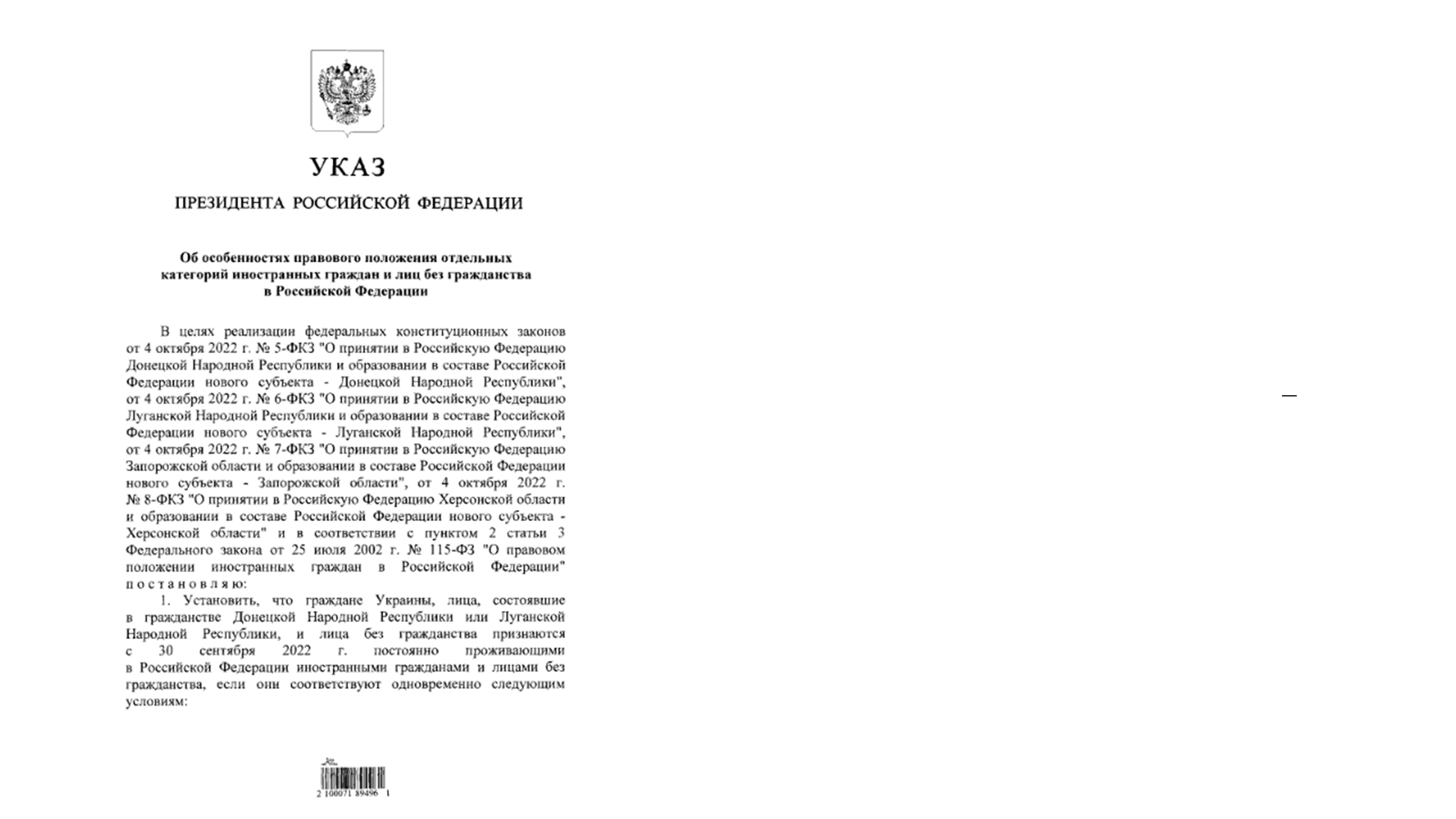

New legislation signed by Putin in April 2023 states that residents who have not acquired citizenship by July 2024 will be considered ‘foreigners or stateless people’, and subject to deportation. “They announced that those who don’t comply will be deported, and their children will be sent to orphanages”, Halyna, a resident of an occupied town in the Zaporizhzhia region wrote in a text message received by journalists reporting in Ukraine. She is too scared to allow her real name to be published, or to be interviewed on camera. “Deportees seem to be left on the road near Vasylivka or Kamianske'', she adds, “but those people disappear, or they are found shot, or forced to dig trenches.”

Denis Pushilin, the acting head of the Russian-occupied part of the Donetsk region, signed an order in June for officials to study the creation of detention centres for “foreign citizens and stateless persons, subject to administrative expulsion from the territory of the Russian Federation, deportation or readmission.”

“There are very clear rules under international humanitarian law of what the occupying power can and cannot do” says Volker Turk, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights. “The situation of the civilian population has to be frozen there, in a protective status,” adds Carlos Castresana, a magistrate expert in international humanitarian law who has worked in several UN Human Rights Commissions. “You can't change people's nationality, you can't change their territory, you can't take out those who were in the territory that was their home and move them against their will somewhere else. And you cannot deploy your population in the territories you have occupied.”

Passportisation is just one of the tools being deployed by the Kremlin through its proxy authorities to ‘Russify’ the occupied territories of east Ukraine. It’s a many-pronged strategy designed to turn the population into Russians, using leverage in every sphere of life. Some have reportedly welcomed Russian rule but it’s not clear how wide support for Moscow goes.

In October 2023 the Kremlin appointed governors for all newly-annexed regions: Denis Pushilin in Donetsk, Vladimir Saldo in Kherson, Yevgeny Balitsky in Zaporizhzhia and Leonid Pasechnik in Luhansk. These political proxies are tried and tested pro-Moscow figures who delivered mandates for Putin from the four territories, in the form of votes in a referendum in 2022 and then local elections in September 2023. Both ballots turned in results in favour of joining Russia.

The people of occupied east Ukraine now face pressure from both sides and for those still loyal to Ukraine this means a near- impossible choice between two evils: to stand up to the colossal Russian state or risk being accused of collaboration with the occupiers. Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy remains staunch in his position of “no peace at the expense of territorial compromises” and early in the war Kyiv strengthened laws to punish activities deemed treason or collaboration with the enemy. It was a knee-jerk reaction to the sight of Russian tanks rolling in through its borders, and the resulting legislation has raised concerns among international organisations.

The UN office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights reports that the law’s lack of definition raises concerns with its legal compliance and “risks arbitrary detention.” Almost 10,000 cases of treason and collaboration have been investigated by the Ukrainian Prosecutor General’s office between January 2022 and September 2023, according to data gathered by the Ukrainian NGO Chesno. When cases are brought to court and the accused are still in occupied territory, they are tried in absentia, often without their knowledge or access to a state-appointed lawyer in Ukrainian territory.

“The law is not good enough, is not clear enough”, says Rashevska, “unfortunately, I think that in the future there could be proceedings in the European Court of Human Rights where Ukraine will be found guilty of human rights violations of people who were recognized by our courts as collaborators.”

This could lead to social conflict between Ukrainians says Antonina Shostak, a lawyer in Zaporizhzhia who assists Ukrainians accused of collaboration with the Russian occupation. “There’s not just a military conflict going on now, we have a conflict between the citizens of Ukraine and those who remained in the temporarily occupied territories, who we can’t reach,” says Shostak. “Firstly, they don’t feel safe, and secondly, they know that in the event of de-occupation, they will be legally targeted.”

PASSPORTISATION

"I swear that I will be loyal to Russia"

In early spring 2023, President Putin urged his administration to "put things into order, and do it quickly," to facilitate handing out of passports in the annexed territories. Mobile and temporary passport offices mushroomed all over the four regions, looking to register as many citizens as possible ahead of local elections in September. Heaps of crisp new documents were issued in record time. By May, over 1.5 million people, according to the Russian Prime Minister, had already received their Russian nationality in these areas.

One telling example of the long-term efficiency of this plan is the self-declared People’s Republic of Luhansk, where in 1991 more than 83% of the population voted in favour of independence from the Soviet Union. As of this summer, three quarters of the population were new holders of Russian passports, according to the Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs.

The most defenceless groups appear to be targeted. Following instructions to prioritise the “passportization of citizens with limited mobility”, Russian officials in military fatigues can be seen in official social media channels visiting retirement homes in Luhansk, or making house calls in Zaporizhzhia and Kherson, where armed men helped seniors with the application and fingerprinting process.

Authorities issue Russian passports in a village in occupied Kherson Kakhovka district, including disabled people. Photo courtesy of Administration of the Kakhovka Municipal District

Authorities issue Russian passports in a village in occupied Kherson Kakhovka district, including disabled people. Photo courtesy of Administration of the Kakhovka Municipal District

When the Nova Kakhovka dam was destroyed in June, occupation authorities reportedly created a two-tier system of humanitarian aid for those affected by the floods, with better conditions for Russian citizens. “During the floods, they approached the people sitting on their house roofs and asked them if they had Russian passports,” says Alexander Samoilenko, Head of Kherson’s regional Council in Ukrainian-held territory. “They didn't have passports, and they didn’t give them any help”. Almost 400 passports were handed out in little over two weeks at the Skadovska temporary accommodation centre for evacuees from the flooded areas, according to the Kherson office of Russia’s Ministry of Internal Affairs. Although initially downplayed by the Russian-appointed governor of the region, Vladimir Saldo, the destruction of the dam proved a golden opportunity for the occupying authorities to increase citizen registration in the Russian system, as thousands of internally displaced people signed up for humanitarian aid.

“A pension is not provided without a Russian passport, food is not provided without a Russian passport, and medical services are not even under discussion”, says Samoilenko.

When a person falls ill in the annexed territories, having the right nationality can literally affect whether you live or die. There are no private insurance companies operating in these areas, and access to doctors and medicines is controlled by the Russian state, which has taken over what was left of the Ukrainian healthcare system.

Larysa Borova fled occupied Kherson and is now living in Odesa. She remembers how a diabetic friend worried about getting her insulin. “They told her, 'next time you come for insulin, you won’t get it without that document'. They were putting pressure, warning her.” It appears to be official policy, judging by posts from the local administration head in the village of Lazurne, Alexander Dudka.

Head of the administration in Lazurne, Kherson, Alexander Dudka says those without a Russian passport will be refused insulin. Photo courtesy of Administration of Lazurne

Head of the administration in Lazurne, Kherson, Alexander Petrovich Dudka says those without a Russian passport will be refused insulin. Photo courtesy of Administration of Lazurne

He can be seen holding what he describes as a list of patients suffering from diabetes. “Here is the first list, 24 people, half of them have neither an individual insurance account number nor a Russian passport. In literally two or three weeks these people will not be able to get free insulin, and they will have big health problems.” He calls those resisting passportisation “those who wait” and warns them: “If these people do not come and submit documents on June 14, then it will be more difficult for them: they will need to prove their citizenship, they will be considered citizens of another country, they will have problems as non-residents.” Ludmila (fictitious name) confirms that the situation is the same in neighbouring Zaporizhzhia. “When you go to a hospital you need to have a Russian passport”, she says. “If you don’t have it, they won’t treat you.”

Once Larysa’s friend relented and applied for Russian citizenship, the insulin became available, and so did her pension. “A person has to live somehow”, says Larysa, “but this is the same thing as a weapon. Sometimes these moral weapons hurt harder than a machine gun. Because the machine gun fires once and it’s done. The moral weapon, when you are pressed every day, it’s very hard”.

Even death becomes difficult for residents. “It is impossible to bury a person without permission from the occupation authorities”, says the Head of Kherson Regional Council Samoilenko. “Burial is carried out with a Russian passport or is denied under any pretext.”

REPRESSION

Torture, death and kidnappings in “Novorossiya”

Swearing the oath of allegiance to Russia is not a matter of choice for people living under occupation, but it doesn’t guarantee a peaceful life. New decrees signed by Putin this year allow the authorities to take away citizenship from those who are critical of Russia's "special military operation," and harsher sentences for treason were written into the law.

“Those who take Russian citizenship can also be expelled or deported in the future, because they are disloyal, or they break other rules and provisions of the Russian legislation,” says Rashevska. “These can be common criminals, but also political prisoners who are transferred to detention centres in the territory of the Russian Federation. Sometimes we don't even know where these people are. Before the full-scale invasion, we calculated that at least 12,000 people were illegally deported from the Crimean Peninsula.”

Artem Petrik lived under Russian rule in occupied Kherson; he says there is no room for dissent in “Novorossiya” or “New Russia”, as these territories are called by the Kremlin, mirroring the situation in mainland Russia. "Everyone was in danger, no one was safe”, says Petrik. “The primary targets were the families of Ukrainian soldiers, police officers, judges, journalists, teachers, and of course scientists, primarily historians. If you want to support or demonstrate Ukrainian identity, you will have big problems: imprisonment, death, torture.” Natalia Rudych describes how tightly the Russian army controlled her city of Melitopol. “Markets were guarded by FSB personnel and soldiers. They would stop and check people whenever they wanted”, she remembers. “Many people were simply abducted in the middle of the street. You could be walking down the street, and you could be taken away without any explanation and driven in an unknown direction. Many acquaintances who were taken have not been located to this day. And this was happening very frequently.”

Former Kherson policeman Anton Lomakin was imprisoned for four months when Russia took over the city. Lomakin says he was tortured in detention. “They simply took the bottom of the T-shirt up on my head, like a mask, completely covering my face. Three or four people stood aside and held my arms and legs. One of them took the water… a six-litre plastic bottle, and slowly started pouring this water on my face”, he remembers speaking from the town of Odesa, where he now lives.

“You begin to lose consciousness and suffocate, going into that world, constantly balancing on the edge between life and death,” added Lomakin “They are pouring, asking ‘Will you answer? Will you answer?’ And you say: ‘Yes, I will, I will’ just to stop the pouring. They release you, you breathe and spit the water. Without time to say anything, they put you down again and start pouring. They keep going like this until you either start to vomit or you start having convulsions, when you simply start to lose consciousness.”

The UN has confirmed “the widespread and systematic use of torture by Russian authorities” in Ukraine, which may amount to crimes against humanity, according to a report by the UN Independent International commission of Inquiry into Ukraine published in late October 2023. “Torture went to the point of death”, says Leonyd Remyga, chief doctor at a Kherson Municipal Clinical Hospital. He was arrested in September 2022 and taken to a pretrial detention facility, where he says he was himself the victim of torture and also gave medical care to other detainees who had been tortured. “Torture was carried out with great skill, physical violence”, he recounts. “Beating knees, fingers, hands, ribs, etc. with a stick. I attended to these people, as a doctor, I saw that they were all beaten, bruised and covered in blood.”

As Ukrainian forces approached to retake Kherson, former policeman Anton was moved first to Hola Prystan, a village on the left bank across the Dnipro River, and then to Chaplynka, a village further south on the way to Crimea. His grandmother Emilia Zasherynska said she looked for him desperately, and when she found his location she registered for a Russian passport to be able to visit him in prison and bring him food. Zasherynska and her husband, who was of Russian origin, had raised their grandson since he was a child, and she is convinced the pressure of seeing Anton in that situation caused her husband to have a heart attack.

“He was very worried, he was nervous, he was marching from one room to another”, she recalls. “He was unable to do anything and then he died and I had to bury him alone.”

Zasherynska says she witnessed the transfer of children from the nearby Oleshky state care home, which in October 2022 was one of the orphanages from which Russian forces reportedly took children and moved them to Crimea and into Russia. “Everything happened in front of my eyes”, she remembers. “How they were taking out children on the boats- packed boats, one after another. Big buses were waiting, and police surrounded the quay in Oleshky to make sure there were no strangers around. They were meeting these children and taking them to Crimea.”

The International Criminal Court has issued international arrest warrants against Vladimir Putin and his Children’s Rights Commissioner Maria Lvova-Belova for the war crimes of unlawful transfer and deportation of children from East Ukraine into the Russian Federation.

EDUCATION

Hearts and minds: Schooling the new Russian patriots

“They said that if we didn't let our children go to that school, they would take them away and would deprive us of parental rights.” said Ludmila, interviewed at a centre for internally displaced people in Zaporizhzhia, with her back to camera to disguise her identity. Ludmila is not her real name, which she requested be withheld for her own security. Together with her sister-in-law Oksana (also not her real name) and their three sons, she recently fled a Russian-occupied town in East Ukraine. After paying people smugglers close to $3000, they embarked on a four-day trip, crossing through checkpoints into Russia, Belarus, and back into Ukraine, where they are waiting for their husbands who are still in occupied East Ukraine. They fled because they didn’t want to enrol their children in the new local school, where teachers brought in from Russia are implementing a curriculum designed by the Kremlin.

Back in the village of Lazurne, in Kherson region, local official Alexander Dudka berates parents who refuse to send their kids to Russian school, saying he knows who they are. “According to the laws of the Russian Federation, these parents will face first civil and then criminal charges”, he says in a video posted in the town’s official Telegram account.

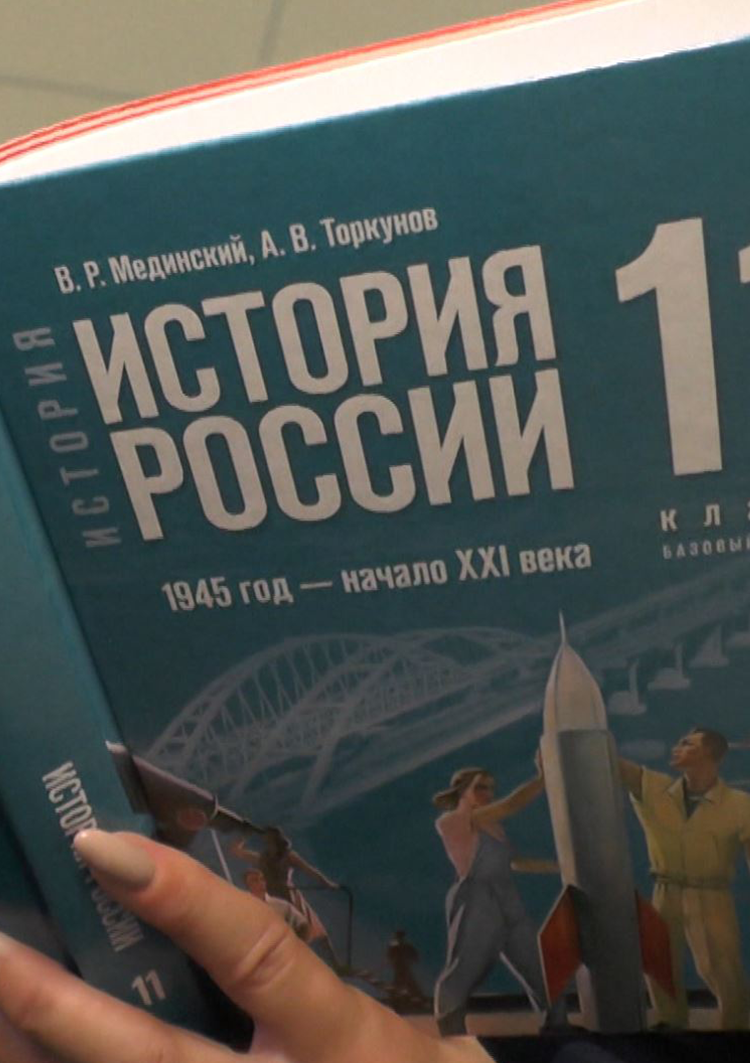

On 1 September 2023, 1,250 schools started the new academic year in the occupied territories, an event marked by local officials with the usual fanfare of the Russian anthem and red, white and blue balloons. Vladimir Putin appeared remotely to address teachers and students in Mariupol. Filmed for state TV, a teacher thanked Russia’s Ministry of Education for a controversial new history book covering the 20th and 21st centuries, aimed at 11th grade students (17-18 years). The textbook was written, proofread, printed and delivered to schools in a record-breaking four months. It offers a new official account of WWII, the Soviet years and Moscow's annexation of Crimea and regions in east Ukraine. It has been criticised by historians around the world for its revision of history, “a blatant attempt to unlawfully indoctrinate school children”, as Amnesty International has called it. “It is an extraordinary tool of propaganda and of transformation and destruction of culture, destruction of knowledge, destruction of history”, says Agnes Callamard, Secretary General of Amnesty International. “It is an entry to multiple violations of (the rights of) children and adults”.

The textbook ends with the “special military operation” in Ukraine, described by Putin in the book as “a matter of life or death, a question of our historical future as a people." This final chapter is key to Russia's argument, says Natalija Arlauskaite, a political science and international relations professor at Vilnius University. It readies the next generation of a nation at war. “A year later, these 11th graders become conscription age youngsters”, she explains. “They will be the ones who will support or not support, understand or not understand, those who are called to war. So this is the first systematic effort to develop an explanation for going to war. Why it should be done, why it is valuable, why it makes sense, why it is important for the country and for this new generation.”

Another new element of the 2023 Russian school curriculum for children from 16 years of age is the return of the basic military training course, reinstated from Soviet times. “The school pays special attention to military patriotic education,” enthused Denis Pushilin, the head of the DPR, at a town hall-style meeting with parents in a school in the Novoazovsky district. “I really liked the military training class, where many visual aids from the battlefields of today's war were collected. At school, words are not different from deeds - five male teachers are now defending the Donbas''.

Aside from learning the basics of patriotism and warfare, these courses offer a starting point for higher education - in Russia. “There are many informative talks with representatives of the FSB, with representatives of military patriotic movements. Children are forced to visit these movements like ‘Yunarmiya’ (Young Army Cadets), parents are forced to send their children to cadet classes,” says Rashevska from the Ukrainian Regional Center for Human Rights. “From these cadet classes, these children can go to the territory of the Russian Federation to continue their education, without any payment or even exams. So for children, it's a good option. Yes, it will be military education, yes, it will be in Russia, but this is some guarantee for their future. So they accept it.”

For parents who want to preserve their children's Ukrainian identity, the only option is covert online classes, which pose a grave risk to those involved. “Russia is also enforcing a very harsh treatment on anyone who dares challenge that writing or reading of history”, says Callamard. “Ukrainian people can be arrested on the basis of the apps they have on their mobile phone. If this is an app which allows children to have access to online education run by Ukrainians and according to the Ukrainian curricula, that is seen as an attempt to dissent and attempt to be different, to reject the propaganda and people are in prison and arbitrarily detained on that basis”.

Tetyana Nadtochii, the principal of a school in Kherson city -retaken by Kyiv in November 2022-, says people in the annexed regions are scared to take Ukrainian online lessons.“ If someone comes to their home and hears that they speak Ukrainian, they can’t do this. They do it in a very limited, clandestine way, because neighbours can also report them,” she says. “They follow the lessons, but they are only a small percentage, only two or three children who connect. Otherwise they risk trouble for the whole family, and we don't have the right to force children and their family to take these lessons online.”

School year in Sevastopol, Odesa starts with a parade and the carrying of the Russian flag.

School year in Sevastopol, Odesa starts with a parade and the carrying of the Russian flag.

The newly-released history book in a school in Sevastopol, Odesa at the start of the 2023/24 academic year.

The newly-released history book in a school in Sevastopol, Odesa at the start of the 2023/24 academic year.

Youngsters participate in an event organized by the Young Army Cadet organization in Mariupol in September 2023.

Youngsters participate in an event organized by the Young Army Cadet organization in Mariupol in September 2023.

Children sworn into youth movement Yunarmia in Donetsk at a ceremony. Photo courtesy via Yunarmia

Children sworn into youth movement Yunarmia in Donetsk at a ceremony. Photo courtesy via Yunarmia

Classrooms like this one in Ukrainian-held Kherson city remain empty as the war rages in the frontlines. Photo courtesy of RSI

Classrooms like this one in Ukrainian-held Kherson city remain empty as the war rages in the frontlines. Photo courtesy of RSI

Ongoing renovation in Mariupol's drama theatre in September 2023. Photo courtesy of Alexander Beglov

Ongoing renovation in Mariupol's drama theatre in September 2023. Photo courtesy of Alexander Beglov

Viktoria Lisogor, former head of Mariupol’s libraries with printed pictures of her Mariupol house, demolished. Photo courtesy of RSI

Viktoria Lisogor, former head of Mariupol’s libraries with printed pictures of her Mariupol house, demolished. Photo courtesy of RSI

Russian construction companies built the Nevsky district in Mariupol, with a school and playground. Photo courtesy of the Russian Ministry of Defense.

Russian construction companies built the Nevsky district in Mariupol, with a school and playground. Photo courtesy of the Russian Ministry of Defense.

RECONSTRUCTION

From the ground up: A reimagined east Ukraine

“The goal is simple and understandable”, Putin said, announcing the allocation of almost 20 billion dollars for the annexed territories in the next two years, “So people feel like part of a big country, and feel all the advantages of this big country for themselves”. Money is being poured into rebuilding cities like Mariupol at dizzying speed. Residents of this coastal town, now a sister city of Putin’s hometown of Saint Petersburg, have seen a windfall of new apartments and transport services, and even received surprise visits from Putin himself.

"The restoration of Mariupol is in full swing, and people have work here”, Ruslan, a builder in the city, told journalists covering the anniversary of the annexation of the new regions, under reporting restrictions established by Russian authorities. Others were less convinced by the new reality, and have mixed feelings. "After the war, recovery is difficult", said Svetlana, a pensioner. “People have lost everything: housing, loved ones. I cannot say that standards of living have become higher. It's still very early to talk about this."

Moscow has made reconstructing Mariupol's theatre a priority project. It is the site of one of the deadliest single Russian attacks of the war, which killed hundreds of people, buried in the rubble of a building being used as a shelter and bearing the word 'Children' written in huge Russian letters. While the theatre is restored, its new troupe of actors is being trained, all expenses paid by Russian and private sponsors, at the Russian State Institute of Performing Arts in Saint Petersburg.

Access to property in occupied Ukraine is limited to Russian nationals, which the Kremlin justifies for security reasons. Those who flee occupation know that in most cases, they will lose forever all they can’t take with them. Natalia Rudych watched helplessly from Kyiv the video stream of security cameras on her building showing a car pulling up and people entering her home in Melitopol. “They took everything from the house. Everything that could be taken was taken. We spent fifteen years building that house, thinking we were building it for a lifetime.” She claims she has since heard from her former neighbours that both her house and her business were taken over by FSB personnel, and that her property has been resold several times.

Holding the satellite pictures of where her house once stood, Viktoria Lisogor, former head of Mariupol’s libraries, can’t hold back the tears. Her building was bombed during the brutal siege of the city and a new complex has been built in its place. “I see my life destroyed. Now I'm realising it doesn't exist anymore. When you don't see it you don't think about it, but when you do see it...it really hurts.”

She has seen the reports done by several news organisations like the BBC or independent Russian outlet Meduza about people from Russia buying apartments and houses in the area, lured by the opportunity of owning a second seaside home. “I don't know if they will be able to stay there, it will depend on their conscience, they haven’t seen the horror”, she says. “Under every ruined building are the bones of people. Right here, in this excavation, are the remains of four of my neighbours because no one has been able to recover their bodies. And this is just my house. Who knows how many houses are left in Mariupol with people who were buried alive under the rubble?”

The Regional Center for Human Rights says it has documented the “colonisation” of Eastern Ukraine since the annexation of Crimea in 2014, in the form of a mass transfer of Russian citizens coming to live there. It's a model they now see repeated in the newly-annexed regions too. “Russian judges, Russian medical personnel, Russian teachers, Russian heads of educational institutions, even Russian businessmen”, Rashevska explains. “In the Crimean Peninsula, we estimate between 600,000 and 800,000 people (came). In the newly occupied territories, the number is lower because the Russian Federation cannot guarantee safety for these people, because the frontline is close.”

In February 2022, Putin justified the invasion as necessary to “protect people who have been abused by the genocide of the Kyiv regime”. Twenty months later, Yale historian Timothy Snyder turns this argument back at the Russian president, accusing Putin of the ultimate war crime. “At a legal level, the aspiration to take Ukrainians and make them Russians is genocidal”, says Snyder, who specialises in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union. “Russification has a destructive element: ‘We have to physically destroy everybody associated with the Ukrainian idea’”.

The Kyiv government describes Russia's military attacks on Ukraine in general as 'genocidal'. “What is it if not genocide when the Russian Federation destroys only civilian infrastructure?” asks Dmytro Lubinets, the Ukrainian Parliament’s Commissioner for Human Rights. “As of now, more than 3200 educational institutions have been destroyed. These are schools, kindergartens. More than 1200 medical institutions. And this all over Ukraine.”

However, most of the legal experts consulted for this investigation said that while crimes are being committed by Russia, they do not qualify as genocide. “The legal definition is quite narrow”, says William Schabas, professor of international and humanitarian law at the Middlesex University in London. “And it's been interpreted by the courts to mean the intentional physical destruction, the extermination of a national, racial, ethnic or religious group. That's the requirement. It's very strict. And it's not that it never applies; it applied perfectly in Rwanda”.

While Russia and Ukraine fight a war of attrition on the frontlines, millions of people in the Russian-controlled land corridor between Crimea and Luhansk wake up every morning to a life where Moscow rules apply. Break or ignore the rules and it can become hard to survive.

A 'Russification' process which started a decade ago in Crimea and separatist-led Donetsk and Luhansk, is now being rolled out across annexed east Ukraine. Putin launched an invasion ostensibly to protect this population; Zelenskyy now demands their return to Ukraine in any peace deal. Whatever the future holds in terms of power politics, people now living under occupation risk being seen as betraying both sides, as they are forced on a daily basis, to adapt to a new reality.

“You live under constant fear, "says Ludmila, now safe in a centre for internally displaced people in Zaporizhzhia. "If you don’t want to be with them, it means you’re against them. And if you are against them, then…” Her sister-in-law Oksana finishes the phrase for her “You go to the abyss, or you watch and wait until they come for you.”

Reporting by Emiliano Bos (RSI), Christoph Bendas (ORF), Louise Jensen (DR), Belen López Garrido (EBU), Indrė Makaraitytė (LRT), Pilar Requena (RTVE), Lili Rutai (EBU), Derek Bowler (EBU) and Alla Sadovnyk (UA:PBC).

Designed and created by Derek Bowler (EBU)

Project Management: Belén López Garrido (EBU)

OTHER INVESTIGATIONS BY THE EBU INVESTIGATIVE JOURNALISM NETWORK

The Missing Children of Ukraine

An in-depth investigation into the forced transfer of children from occupied Ukraine to Russia. The Kremlin says they're saving them, while Kyiv claims genocide. The International Criminal Court has issued arrest warrants for war crimes related to these transfers.

Who owns European Football?

Billions of euros are flowing into the "beautiful game", mostly from non-European sovereign and private investment funds. We investigate the new football ownership systems across the continent and the consequences on the sport, the players, and the fans.