Hammer and sickle

Soviet propaganda in occupied Ukraine

As a march sounds from a loudspeaker in early May 2022, in the occupied Ukrainian city of Melitopol, the occupiers have chosen to hoist in the centre of the city not the Russian flag, but the Soviet banner – a red cloth emblazoned with the sickle and hammer.

That march, which eventually falls silent, is ingrained in people born in the Soviet era. It has a name - 'Holy Struggle'. The march was released in the summer of 1941, when the Soviet state needed propaganda tools to support them in the war against Nazi Germany and is often called the “anthem of the Second World War” or Great Patriotic War as it is called in Russia.

The Soviet Union disappeared in 1991, but the Kremlin is using Soviet symbols to consolidate its power in the Russian-occupied Ukrainian territories in 2022. The Soviet flag and the Soviet march in Melitopol are just some examples of this.

Ukrainian historian Artem Petrik, who lived in Kherson under Russian occupation, describes the Russian forces occupying east Ukraine today as a terrifying amalgam of their historical antecedents. "What did we see when they came?”, he said. “A symbiosis of people who came to us from the times of Ivan the Terrible, prototypes of the Red Army soldiers of 1919 that Lithuania faced during the struggle for independence, who once came to conquer Lithuania and the Baltics, and, of course, characters from Stalin times," says Petrik.

He has been working at Lithuania's Klaipeda University for several years. When war broke out he was in his hometown of Kherson, where he was staying with his parents while he finished his new book on the history of the Baltic states. He didn’t have time to leave Kherson and remained there throughout the Russian occupation until November 2022. He concealed his identity and constantly changed accommodation; even those closest to him didn’t know where he was hiding.

"If you wanted to keep your Ukrainian identity under the occupation, you faced imprisonment, torture and death," he says. “I had to hide all the time and it was a very difficult, but also very interesting experience.”

He lived through the occupation, collecting evidence of Russification in the areas under Moscow's control, a strategy which continues today. He shows a bundle of newspapers.

In the spring of 2022, the Russian occupation authorities revived the publication of the local official gazette, which had been defunct for some time. It kept its name, Naddnipriyanskaya Pravda, but in a “Russified” version. Throughout the newspaper’s history, including during the Soviet years, its name was spelled in Ukrainian.

Alongside this official journal, the Russian authorities started publishing Komsomolskaya Pravda, which was distributed throughout the Soviet Union, until its collapse in 1991. Since then publication continued only in Russia, and Belarus. Komsomolskaya Pravda is sanctioned in Ukraine and Canada, the latter for its involvement in the deportation of Ukrainian children to Russia and the dissemination of propaganda and disinformation.

Both newspapers are examples of an official policy of Russification in the occupied Ukrainian territories, with the aim of assimilating these regions into Russia.

The pages of Komsomolskaya Pravda are adorned with the black and orange stripes of the St George ribbon, a symbol of victory over fascism during the Great Patriotic War. The ribbon, together with the capital letters Z and V, are central visual elements of Moscow's campaign supporting its war in Ukraine. In Baltic countries, this stripe is considered a symbol of Russian imperialism and is banned.

Naddnipriyanskaya Pravda’s masthead is framed by the Soviet Order of Honour on one side and a new Russian-inspired coat of arms, created especially for the occupied areas, on the other. The 9 May, 2023 edition of Komsomolskaya Pravda of Kherson Region contains a huge congratulatory message on the day of victory in the Great Patriotic War.

"Nothing will overshadow our most important celebration - in a land liberated from fascism 78 years ago, a new generation is now fighting a heroic war. We appreciate the heroism of our grandparents and are proud of the heroes of today," reads the text box on the photo.

On the left side of the page was an article about Russian President Vladimir Putin’s speech, promising economic advantages, aimed specifically at the socially disadvantaged. “It is important not only to rebuild what has been destroyed but also to develop the economy" he said, pledging that "all pensioners will get bank cards".

Every issue contains statements from Putin, and one of the 2023 issues is almost entirely devoted to the visit of Sergei Kiriyenko, Deputy Chief of Staff of the Russian President, to Russian-occupied Kharkiv.

"Sergei Kiriyenko sets the course for the development of Kherson region", reads the headline. The news coverage stresses that "During his visit to Kherson region, the First Deputy Head of the Administration of the President of the Russian Federation discussed with local authorities the main directions of the region's development, including modernisation of kindergartens, schools, and cultural institutions, preparation for the new school year, children's health, strengthening of the control over value education".

Front page of the Komsomolskaya Pravda journal with St George ribbon.

Front page of the Komsomolskaya Pravda journal with St George ribbon.

Komsomolskaya Pravda issue from May 2023 featuring the header "one state", the St George ribbon and carnation, symbols of the Soviet Union.

Komsomolskaya Pravda issue from May 2023 featuring the header "one state", the St George ribbon and carnation, symbols of the Soviet Union.

Naddnipriyanskaya Pravda issue reports the visit to Kherson of the Russian official Sergey Kiriyenko.

Naddnipriyanskaya Pravda issue reports the visit to Kherson of the Russian official Sergey Kiriyenko.

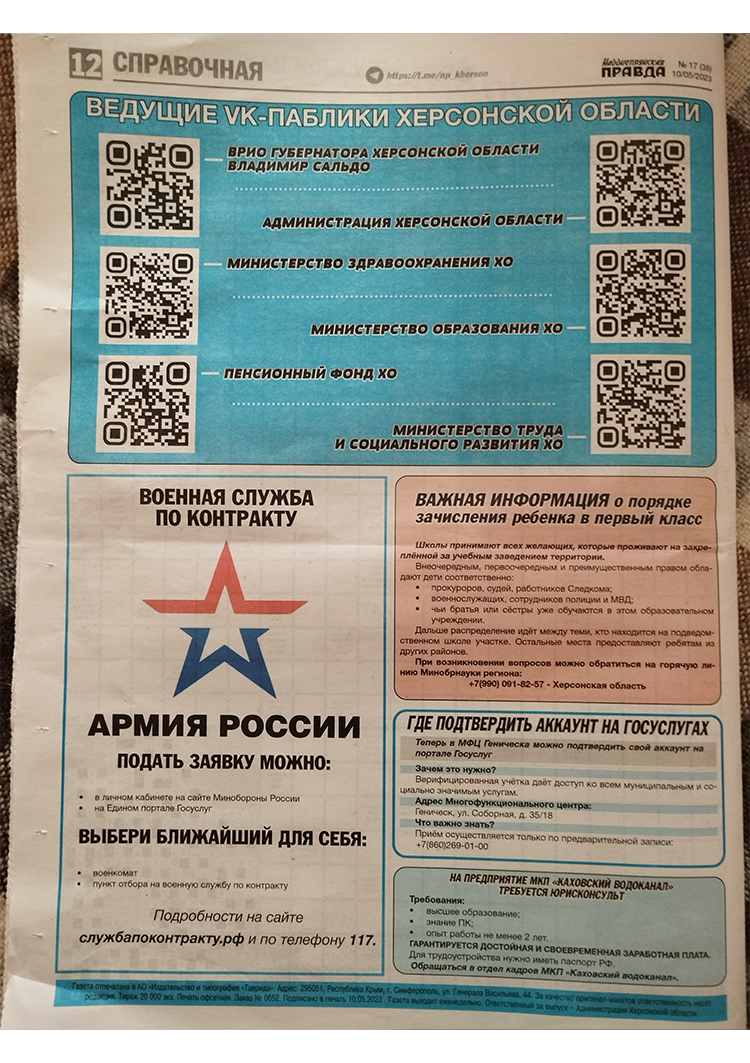

Naddnipriyanskaya Pravda issue from 10 May 2023 featuring an ad for the military service in the Russian army

Naddnipriyanskaya Pravda issue from 10 May 2023 featuring an ad for the military service in the Russian army

The Naddnipriyanskaya Pravda masthead framed by the Soviet Order of Honour and a new Russian-inspired coat of arms, created especially for the occupied areas.

The Naddnipriyanskaya Pravda masthead framed by the Soviet Order of Honour and a new Russian-inspired coat of arms, created especially for the occupied areas.

Soviet symbols for a new Russian empire

Petrik says it is no coincidence that Soviet images, symbols and narratives are transferred to the societies of the Russian-occupied Ukrainian territories.

“In simple terms, the Russians are looking for a chain, a rope to bind the peoples of the empire together. To do this, they use the old symbols and ideology of hatred," says Petrik, who experienced first-hand the occupation.

"When we are confronted with a change of political regime, there is usually a symbol workshop at the same time - because there is a search for symbols,” said Natalija Arlauskaitė, Professor of International Relations and Politics at Vilnius University. “They are very mixed. Usually, the symbols come from a variety of contexts, which can be both relevant in that environment, and sometimes they are born completely spontaneously.”

She suggests the raising of the Soviet flag to the sound of a Soviet World War II march, in May 2022 in occupied east Ukraine, is precisely such a mix of symbols.

“It is a resource associated with that just victory, which is used in a new situation”, said Arlauskaitė. “The symbolic ideological imagination is largely a retro imagination, which is why the whole arsenal of symbols that were accumulated during the Soviet era is appropriate here. It is used in combination with contemporary pop culture to create these hybrid constructions. These constructions are sometimes macabre, but they are there”.

Symbols of Soviet times have survived longer in Ukraine than in the Baltic States. In the Ukrainian capital, Kyiv, and elsewhere in the country, statues of Soviet figures and symbols in public spaces were only recently removed, after the 2022 Russian invasion. Monuments reflecting Russian history and culture are also being torn down.

More than 60 monuments and other objects have already been demolished as part of a process of 'decommunisation' in Kyiv, according to statements to Euromaidan Press by Hanna Starostenko, deputy head of the state administration of the city. "Monuments and memorial plaques commemorating the Soviet and imperial past have no place in the capital”, she said according to the article. “Together with experts and representatives of specialised institutions, we are carrying out extensive work to permanently remove from public space all those objects that glorify the aggressor country.”

These symbols are present in everyday life in the occupied territories, and for those who lived under the Soviet occupation in the past, the images coming now from the occupied territories of Ukraine bring back memories of the Soviet army entering their countries.

"They did the same thing, but now with even more brutality towards Ukraine. They filled the trenches full of people. And we were strangled for a while, taken to Siberia”, says Ona Butrimaitė - Laurinaitienė.

A Soviet political prisoner, she witnessed the Soviet occupation of Lithuania in 1940 and then again in 1945 with her own eyes.

“Everywhere was filled with bodies: cemeteries, toilets, wells."

She says she sees similar tactics employed by the Russian army in Ukraine today.

"In Ukraine they also dug trenches full of people with their hands tied. Tortured and buried. The same style, the same technique."

For Dmitry Oreshkin, a Russian political analyst who is in exile in Riga, Latvia, the current Kremlin regime is replicating the Soviet policy it applied in the territories it occupied in the Baltic region, first in 1940, then in 1945.

"Ideologically, it is the same, because the people who grew up in Lubyanka, whether they want to or not, are carriers of the same Soviet discourse. What else can they do?", he asks. "Of course, some differences can be found. But the Kremlin regime's ambition is to homogenise the population. Stalin pursued this policy in a targeted way. He knew that to subjugate a nation, it was enough to destroy the 2-3% of the most active, educated, and motivated people. And with the rest, you can do whatever you want."

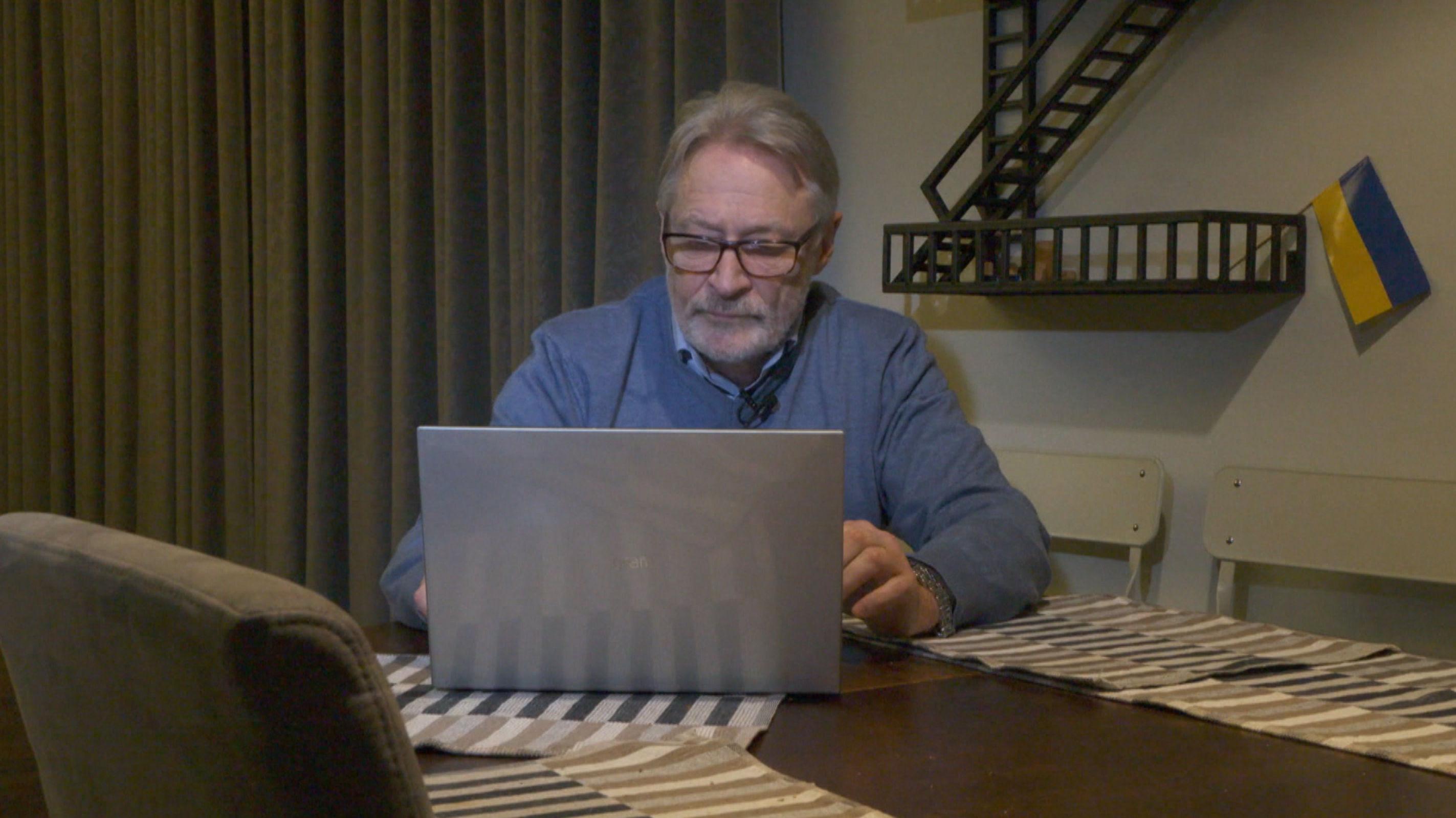

Russian political analyst Dmitry Oreshkin. Photo by EBU

Russian political analyst Dmitry Oreshkin. Photo by EBU

In the Baltic States, the Soviet occupation in both 1940 and 1945 began with the deportation and repression of indigenous populations. Russia’s current policy in Ukraine seems based on the Soviet experience in its occupied territories.

Oreshkin recalls his father's stories from the Second World War about how the Soviet forces were received by the inhabitants of the occupied territories.

"My father told me that when you enter the city you are greeted with flowers, but when you leave the city they shoot you in the back”, he recalls. “Therefore, the inevitable consequence of the occupation is the cleansing of the so-called hostile elements. Anyone who has an opinion or says something independent is, by definition, an untrustworthy element, so the purge becomes total. People must be singled out, expelled, and persecuted. As a rule, the most active people are local and do not speak Russian. So efforts are made to attract migrants to take the place of the people who have been expelled or repressed, to make the population more loyal. This is commonly referred to as ethnic cleansing. And it is inevitable", explains Oreshkin.

The scholar is also reluctant to refer to what is happening in the occupied territories of Ukraine as mere Russification."It is obvious that Russification is taking place. But it is not exactly what I would call Russification," Oreshkin said. Russia's actions in the occupied lands of Ukraine seem to him to be the Sovietisation of Ukraine.

"From the outside looking in, it is called Russification, but it was not all bad in Russia”, he concludes. “There were elections in Russia, but there were never elections in the Soviet Union. We are going back to the Soviet practice of fabricating everything. Violence, intimidation, and the creation of a new elite are happening fast. And the aim is the same: to keep power by any means necessary.