The empty orphanages of Kherson

First came the army. Then the Russian bureaucracy. Soon the children were gone.

14/02/2023 -They arrived after midday, just as children in the Stepanivka center for social and psychological rehabilitation, in Kherson, were having lunch. Dressed in military fatigues and holding rifles, the Russian soldiers went into the building, led by a man reportedly from the FSB, Russia's secret police.

They entered the administration office and went through the children's files, computers and footage from the security cameras. That's when Volodymyr Sahaidak, the director, knew his fears of children being taken away were not unfounded. He had heard the stories of minors transferred into Russia since the start of the occupation of Crimea and the Donbas in 2014, and now that Kherson had fallen, he worried about the fate of the youngsters under his care, according to an interview with Sky News. "We saw Russian propagandists saying that they needed to take the children to give them to military schools, indoctrinate them and let them fight for Russia," he said. "It was the scariest thing so we started hiding children because we understood they would take them."

Sahaidak started looking for ways to protect the 52 orphaned and vulnerable children under his care. He placed several of them away from the institution, with seven of his staff. Others were sent to live with distant relatives, and he kept some of the older ones with him.

After looking through the different areas of the building, the soldiers ended up not taking the remaining children in the center, but later brought a group of 15 other minors from elsewhere in Ukraine into the Stepanivka center. The staff took care of them, until one day the Russian forces came back, put the children in military vehicles and drove off without revealing their destination.

Russian soldiers are seen in the security cameras of the Stepanivka care center in Kherson entering the building and looking at the children in the dining room. Video obtained by Yle News (Finland)

Russian soldiers are seen in the security cameras of the Stepanivka care center in Kherson entering the building and looking at the children in the dining room. Video obtained by Yle News (Finland)

On 30 September 2022, Vladimir Putin triumphantly signed the annexation of four new regions into the Russian state: the Ukrainian occupied regions of the self-declared Donetsk People's Republic and Luhansk People's Republic, and the areas of Kherson and Zhaporizhia. Among the selected few attending the Kremlin event was Maria Lvova-Belova, Russia's Children's Rights Commissioner. She promptly took to social media to officially welcome the children from these territories into the Russian state. “Children of the DPR, LPR, Zaporizhzhia and Kherson regions are now Russians. Congratulations, friends! We are happy to welcome you into our big family!”, she captioned a selfie from the event in her Telegram account.

Maria Lvova-Belova attending the Kremlin event to celebrate the annexation of four regions of Ukraine, 30 September 2022. Photo: Telegram channel of Lvova-Belova

Maria Lvova-Belova attending the Kremlin event to celebrate the annexation of four regions of Ukraine, 30 September 2022. Photo: Telegram channel of Lvova-Belova

But on the ground, fighting was still raging between Russia and Ukraine, and particularly in Kherson, where evacuations were being planned by Moscow. They prepared for an attack by Ukrainian forces looking to retake the area and the only regional capital Russia had been able to occupy since the start of the invasion. What happened at the local Oleskhy state care institution for disabled children there is an illustration of one of the ways in which children from boarding houses around Ukraine are transferred into Russian-controlled territory.

The Oleshky state care boarding house in Kherson. Photo: Capture from UA:PBC regional station, January 2021

The Oleshky state care boarding house in Kherson. Photo: Capture from UA:PBC regional station, January 2021

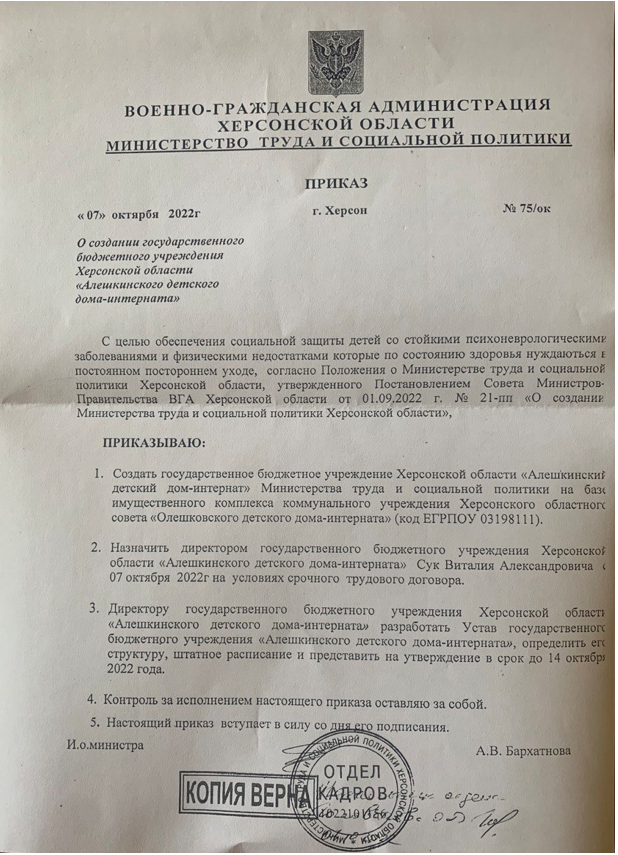

One week after the official annexation, on October 7, the pro-Russian administration of occupied Kherson issued an order appointing a new director of the Oleshky orphanage-boarding school, “to ensure social protection of children with persistent psycho-neurological diseases and physical disabilities”. According to Ukrainian authorities and press reports, there were 82 children in the institution, 40 of them under palliative care for serious illnesses or conditions.

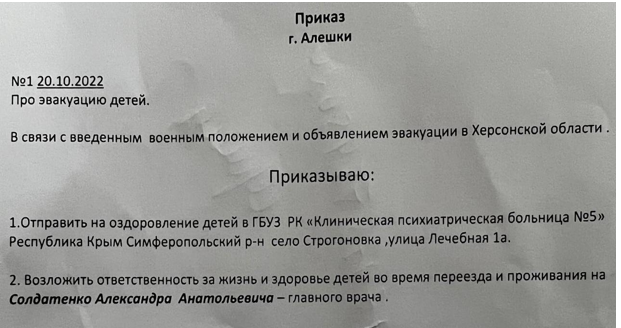

Soon after, another order was issued to send the children to the state budgetary health care institution Psychiatric Hospital No. 5 situated in Simferopol, in the Republic of Crimea, for "rehabilitation”, in connection with the martial law and the wider evacuation of the region.

Three days later, on October 23, the head of the office of the President of Ukraine, Andriy Yermak, reported that the Russian occupiers had taken 12 children from Oleshky to the Psychiatric Hospital No.5 in the village of Strogonivka in Simferopol, in occupied Crimea.

Dmytro Lubynets, the Verkhovna Rada's human rights commissioner confirmed a week later the removal of children in another Telegram post which seemed to show the redacted list of children.

Russian confirmation didn't take long. On November 12th, the Russian ombudswoman for children Maria Lvova-Belova posted pictures of what she called the “relocation”, saying it was too close to the frontline and explaining that the children were now “in a safe area”.

“It was too close to the frontline", she said in her Telegram post. 52 children with severe pathologies. Almost all cannot move independently, five are in wheelchairs. Specialized transport was needed for the evacuation. After discussing the situation with colleagues from the Russian Ministry of Health, ambulances were promptly sent from Sevastopol. Now the children are in a safe area."

Oleksandra Romanstova, from the Ukrainian Center for Civil Liberties and Nobel Peace Prize 2022, says this case illustrates how Russia is going about transferring children under Ukrainian state guardianship, and questions the argument that they do it for the welfare of the children. “I have direct knowledge of Oleshky because my university has been supporting it for more than ten years”, she said in an interview in January in Kyiv. “And we know precisely that all of these 30 children from this orphanage -which is now controlled by Russian forces- , all of them were brought to the territory of Crimea, and they put them in a psychiatric hospital there. So they were not put in a rest camp or similar place, it's not exactly a nice place for such children, who need support, but not in this way.”

The Oleshky center remains, as of February 2023, under the area of Kherson still under Russian occupation, West of the Dnipro river. Ukrainian authorities say they do not have knowledge of the fate of any remaining children who could be housed there or moved to Crimea.

Document from the Military Civil Administration of Kherson region, Ministry of Labour and Social Policy, creating a new administration for the institution, now under Russian authority.

Document from the Military Civil Administration of Kherson region, Ministry of Labour and Social Policy, creating a new administration for the institution, now under Russian authority.

Evacuation order for the children of the Oleshky orphanage

Evacuation order for the children of the Oleshky orphanage

Telegram post by Maria Lvova-Belova detailing the transfer of children from Oleshky.

Telegram post by Maria Lvova-Belova detailing the transfer of children from Oleshky.

Psychiatric Hospital No.5 in Simferopol

Psychiatric Hospital No.5 in Simferopol