Stas' journey: From a Ukrainian orphanage to a Russian family

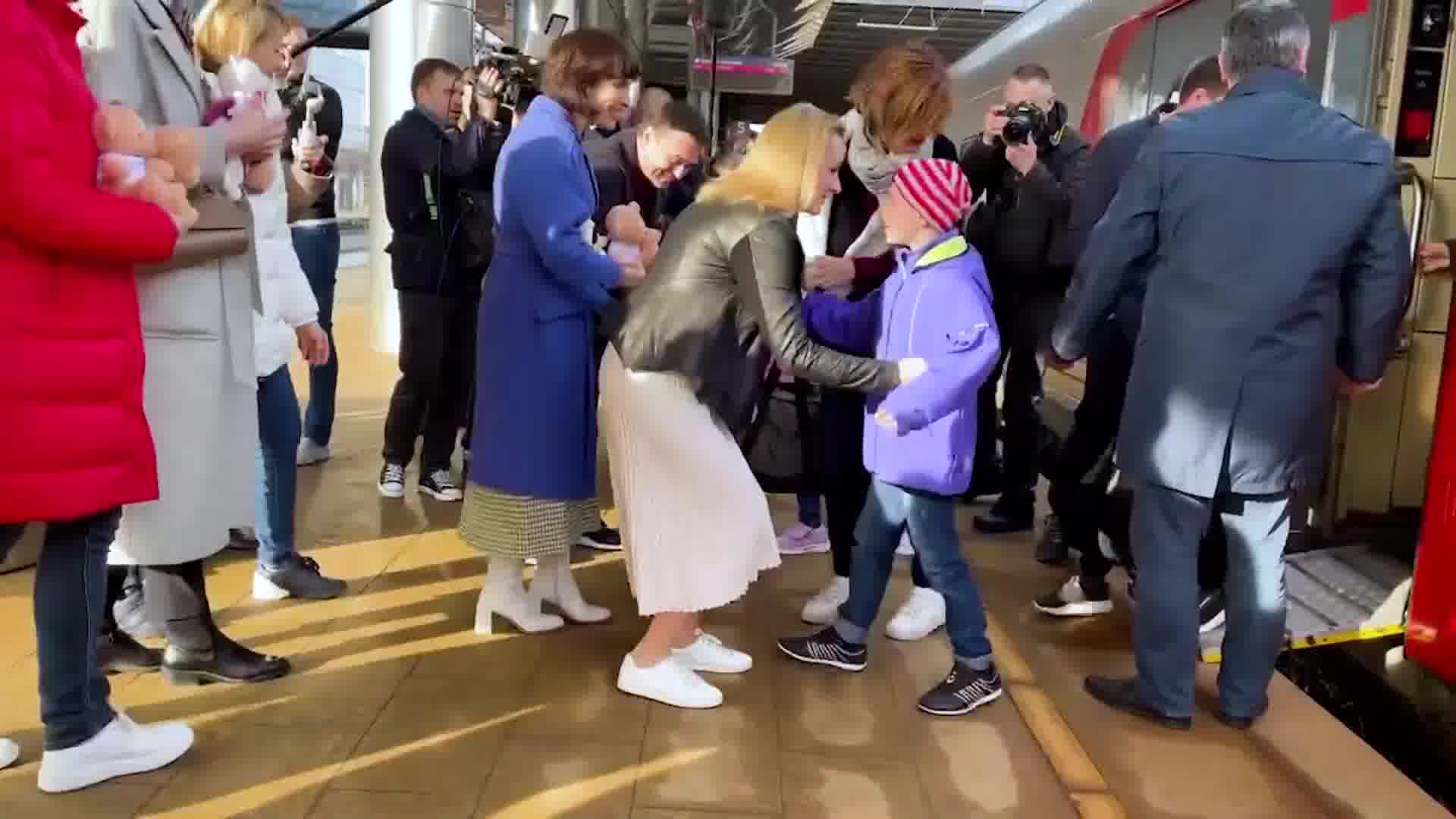

On a warm spring day, a crowd has gathered on the platform of Moscow's Aprelevka railway station, to meet the children transported from warzones in east Ukraine to Russia, where new homes and an uncertain future await them.

14/02/2023 With a burst of patriotic balloons in the colours of the Russian flag, Russia's Children's Rights Commissioner, Maria Lvova-Belova, and Moscow Oblast Governor Andrey Vorobyov step forward to greet the young passengers from the Donbas region of Ukraine.

This event, staged for the cameras of Russian state media, is designed to favour two ambitious politicians, playing their part in Vladimir Putin’s war on Ukraine and eager to cement their position as Kremlin favourites.

Panning through the carriage full of children, the camera lens elicits some smiles, but other children look apprehensive as their journey to Moscow and into the unknown nears its conclusion.

In a corner of the carriage, a young boy sits quietly with his drawing things, taking refuge in his created world.

Stas shown with his drawings inside the train that took him to Moscow on 23 April 2022. Photo from Moscow Governor YouTube channel

Stas shown with his drawings inside the train that took him to Moscow on 23 April 2022. Photo from Moscow Governor YouTube channel

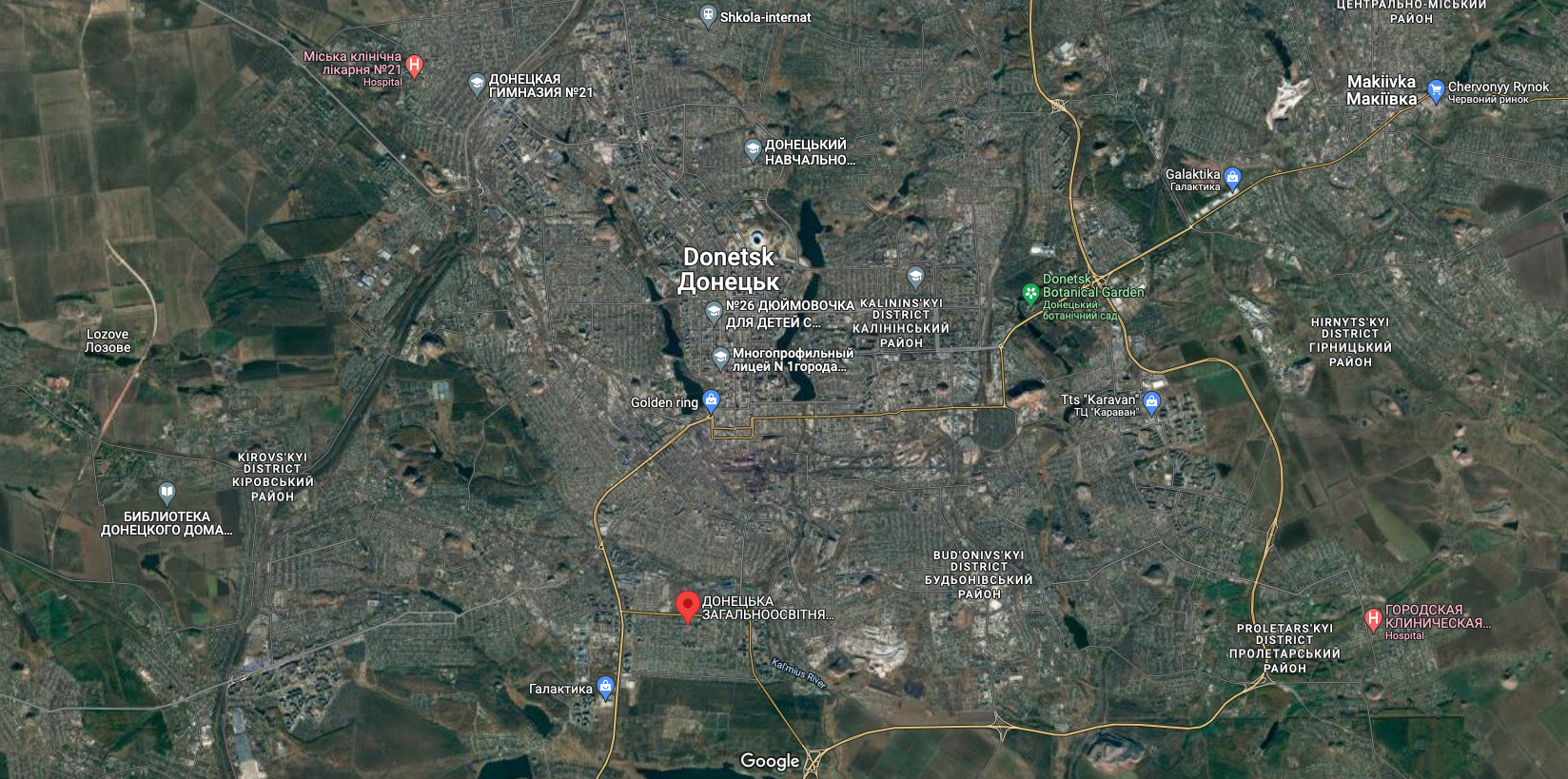

Stas, aged 9, was plucked out of his former life in a boarding school for children in state care in the Russian-controlled Donetsk region and sent to Moscow, where he was promised the love and warmth of a new family and a chance to become Russian.

The train pulls into Aprelevka, and the children collect their few possessions, clinging to them as reminders of the place they once knew as home.

Stas' journey from state care in occupied territory in Ukraine into a Russian family is part of what Ukrainian authorities have denounced as a Kremlin operation to deport Ukrainian children and fast-track them into becoming Russian citizens.

Since the start of the war, Russian state officials have reported numerous transfers of unaccompanied Ukrainian children to what they described as loving families eager to help them overcome the trauma of war.

Stories of rescue and happy endings that are, however, in full breach of international law "Just to be very clear: there is no excuse for doing this", says Bill Van Esveld, Associate Child Rights Director for Human Rights Watch. "The Russian propaganda line is that 'we are doing this to protect these children. We're helping them. They were neglected by their parents. They were abandoned. And now we've taken them for their safety and their health'. That's not good enough. You can't take another country's children away during wartime, split them off from their families. They say that these are orphans who are being saved from war. In fact, many of these kids have families. They have parents with full parental rights and they were taken away without the parents ever being notified who are now desperate to get them back. So if you want to help these kids, release them. Don't take them out of their country and allow them to cross to Ukrainian controlled territory."

Stas’ new foster parents also took in his twin sister Dasha and an older 12-year-old sister, Nastya. The siblings had been separated for more than two years, living in different care facilities in occupied Ukraine.

When they met again at the station on that warm April day, they hugged each other tightly, hanging onto familiar faces in an unknown world.

Their new ‘guardians’ Galina-Valeryevna Bogachyova and her husband, Alexander Bogachev, greeted the siblings on the platform, waving Russian flags.

The Bogachevs told Russian media they had been eager to reunite the two sisters with their brother.

Stas is welcomed by his siblings, his new foster mother Galina-Valeryevna Bogachyova and Maria Lvova-Belova.

Stas is welcomed by his siblings, his new foster mother Galina-Valeryevna Bogachyova and Maria Lvova-Belova.

"When we found out about this situation, we immediately responded", Bogachyova said, referring to the case of the separated siblings. "We were one of the first to send our questionnaire and video clip. We really wanted to host these guys", she told journalists, reporting from the train station.

"We have a unique situation because the two girls, whom we took before, we have only had them less than a day, but they are already family, Dasha and Nastya," Bogachyova said, adding she was overwhelmed by emotions.

She proudly showed the children photos of their family on her Instagram. The Bogachev family home in Domodedovo, 37km southeast of Moscow, looked like a lively household, with two biological and four fostered children shared by the couple.

Stas' story began at Donetsk Boarding School No. 1, a boarding school for orphans and children in state care. The school's director, Olga Volkova, accompanied the children on their journey to Aprelevka, telling Russian media the school, home to 225 children, had been evacuated on February 18 amid rising tensions between Russia and Ukraine.

Volkova said children and teachers were taken to a sports and recreation complex near the Ukrainian border in Russia's Rostov region under instructions from the Ministry of Education and Science of the DPR (the self-declared Donetsk People's Republic). .

"When we left Donetsk, all the children were looking forward to our return home because, as I said, the Donetsk Boarding School is a home for children. But every child wants warmth, the care of a mother and father so when they found out they had to go to new families, we talked with the children: 'If, God willing, everything works out, will you agree?' The children, of course, gave their consent," Volkova told Russian internet outlet 360 News.

Led from the platform hand in hand with Lvova-Belova, Vorobyov and their new guardians, the children assembled inside the station, a captive audience for the politicians.

Lvova-Belova is herself a mother of five biological and four foster children, and guardian of 13 disabled children living in accommodation provided by several charitable organisations she has founded.

"There is a family who is taking three kids, two of them arrived from Kursk yesterday, and one of them is arriving today. The twin siblings haven't seen each other for two years,” she said, beaming with pride.” Can you imagine these emotions? Very strong."

Lvova-Belova confirmed the sisters had arrived just 24 hours before their brother Stas, travelling to Moscow from Kursk. She gave little information on how Dasha and Nastya were transported to Russia beyond saying their foster papers were prepared by local authorities in Russian-occupied Donetsk. When Stas and his sisters were brought to Moscow in April, Russian law only allowed the children to be fostered. Since that time, Putin has introduced new legislation facilitating the path to Russian citizenship for unaccompanied Ukrainian minors.

Stas and his sisters Dasha and Nastya embarked on their new life in Domodedovo and were not seen until July when they appeared alongside Vorobyov and Lvova-Belova at a ceremony in Moscow, among other orphans from Donetsk who received Russian citizenship.

On a balmy summer day in one of Moscow’s parks, clutching teddy bears and ice creams, the children were presented with embossed red envelopes - inside, new birth certificates granting Russian citizenship.

This would be a reset for the children, declared Vorobyov, allowing them to move forward and "ensure all the bad things are left behind.

Russia allows its citizens to keep a Ukrainian passport, as long as they notify the relevant authorities. Ukraine is one of only 26 countries in the world who does not recognize dual citizenship. In the wake of the occupation of Crimea and other Ukrainian territories, President Zelenskyy recently introduced legislation in Parliament to allow Ukrainian citizens from those areas to keep their Ukrainian nationality, since "Ukraine does not recognize the forced automatic acquisition of Russian citizenship by Ukrainians in the occupied peninsula, and this is not a reason to lose Ukrainian citizenship", according to its Foreign Ministry.

It is unclear, however, how the acquisition of Russian nationality while in Russia would impact the Ukrainian citizenship of minors like Stas and his sisters.

Stas, his sisters and other children from the Donbas receive their Russian passports at a ceremony in Moscow on 5 July 2022. Video from Lvova-Belova Telegram account.

Stas, his sisters and other children from the Donbas receive their Russian passports at a ceremony in Moscow on 5 July 2022. Video from Lvova-Belova Telegram account.

The siblings would become the poster children for Lvova-Belova’s initiative, appearing regularly with Vorobyov, showcasing their apparent integration into Russian life.

The story of the reunited siblings from Donetsk was taken up by state media, promoting a picture of Russia’s efforts to save a generation of children not just from the horrors of war, but from a miserable life in Ukraine.

In an interview at the family home, the Russian TV audience finally learned the story of how the siblings found themselves in state care in Ukraine. Nastya, the eldest of the three, said her biological mother had sent them to an orphanage as she could no longer afford to feed them. There she and Dasha had become separated from Stas for more than two years before their emotional reunion on the platform at Aprelevka.

Stas and his family at a Moscow patriotic festival. Video: Moscow Governor's YouTube official channel.

Stas and his family at a Moscow patriotic festival. Video: Moscow Governor's YouTube official channel.

Vorobyov’s office documented Dasha and Stas' 9th birthday celebrations at Moscow’s ‘Walk the City’ festival. The newly-Russian children were paraded through the patriotic event dedicated to Russia’s military history from the 16th century to key battles of World War II, known as the "Great Patriotic War" in Russia, and referenced by Putin in an attempt to justify his invasion of Ukraine.

But a video of the momentous day published weeks later tells a more vivid tale of Stas' new life. In the footage, fireworks explode at the end of the day’s celebrations, reminding the boy of the terrors of his life under Russian shelling in Donetsk, their crashing sound like missiles hitting their targets.

"No, no, no, it's fireworks. Wait a couple of seconds; my little bunny," Bogachyova says; "No, it's not a bomb," she tries to reassure him as tears stream down the little boy’s face.

Photo shoot showing Stas, his sisters and the extended Bogachev family, as portrayed in a propaganda video telling their story.

Photo shoot showing Stas, his sisters and the extended Bogachev family, as portrayed in a propaganda video telling their story.

The estimated number of deported Ukrainian children to Russia has surpassed more than 13,000, while 800 children are believed to have died or disappeared in the process of deportation, according to Ukrainian authorities.