The origins of the investigation

In early October 2022, in the sidelines of the Prix Italia in Bari, Italy, a reporter from the investigative unit of Ukrainian public service broadcaster UA:PBC called Alla Sadovnyk showed a video on her phone to some journalists attending a workshop of the EBU Investigative Journalism Network.

It showed a train full of Ukrainian children, described as “orphans” in the accompanying caption by Russian authorities. They were arriving in Nizhny Novgorod, 400 kilometers from Moscow, accompanied by Maria Lvova-Belova, the Russian Children’s Rights Commissioner.

There were many other children like these being taken out of occupied Ukraine and into Russia, the journalist said, and many of them had families who were desperately looking for them. She asked the network for help in looking into this story.

Several members expressed interest, and a reporting group was formed to investigate the story. The group included journalists from France Télévisions, RSI Switzerland, UA:PBC Ukraine, RTVE Spain and was coordinated by the EBU in Geneva.

During the following four months we held online meetings almost weekly.

We exchanged intelligence, sources, and plans for coverage, sharing the workload of the research for the different angles of the story.

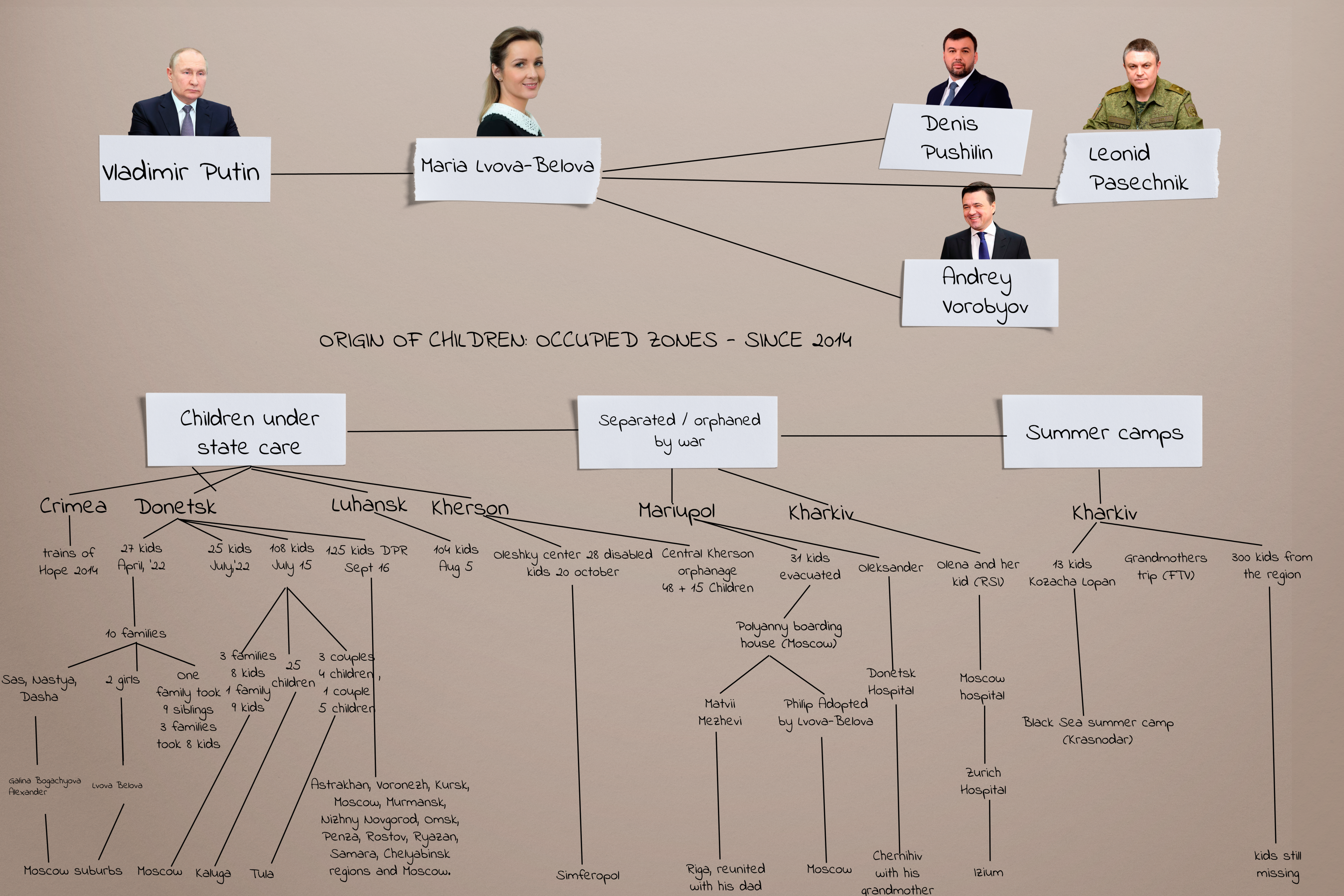

The Eurovision Social Newswire team had the key task of sourcing and verifying the material published by authorities and other Russian sources that showed the scale of these transfers- at times more than one hundred children were being brought together from occupied territories of Ukraine, given Russian citizenship and placed in Russian foster families or state care houses and so-called “summer camps”.

The videos were publicly available, as the Russian government embarked on a publicity campaign to present this as a charitable effort to save children from war and offer them a better life. With the help of Russian speakers, the teams combed social media and other official accounts and started gathering visuals of these deportations.

A digital timeline was built to store and display the evidence and link to the different sources, with more than 80 pieces of content.

Poring through the images, cross-checking dates and locations, it soon became clear that this was a systematic effort, with a legal, administrative, and financial structure supported by Vladimir Putin himself and executed by his Children’s Rights Commissioner Maria Lvova-Belova.

The study of the videos and other official accounts showed the magnitude and the playbook for the transfer of children from occupied Ukraine into Russia.

The study of the videos and other official accounts showed the magnitude and the playbook for the transfer of children from occupied Ukraine into Russia.

Meanwhile, first-hand accounts were coming from the ground.

Agnes Vahramian from France Télévisions and Emiliano Bos from RSI went to Ukraine and worked on the stories of parents separated from their children.

Reporters from the Belgian broadcaster RTBF filmed interviews in Kyiv for this story, while they were there on another assignment.

We interviewed the Ukrainian Children’s Rights Commissioner as she passed through the WEF in Davos. Alla Sadovnyk from UA: PBC helped with contacts, information on orphanages and gathered statements with sources on the Ukrainian side.

Pilar Requena from RTVE dived into the legal ramifications of the story.

Yle in Finland provided the visual evidence of the emptying of one orphanage in Kherson by Russian troops.

After a security assessment, the EBU Moscow bureau asked for interviews with the Russian authorities. They are yet to respond.

France Télévisions Agnès Vahramian with Ukrainian mothers who sent their children to Russian camps.

France Télévisions Agnès Vahramian with Ukrainian mothers who sent their children to Russian camps.

UA:PBC reporter Alla Sadovnyk and RSI reporter Emiliano Bos met in Rivne, Ukraine while Bos was filming the story of a mother separated from her son.

UA:PBC reporter Alla Sadovnyk and RSI reporter Emiliano Bos met in Rivne, Ukraine while Bos was filming the story of a mother separated from her son.

By early February, we were ready to put all the elements together and publish. The digital and broadcast content gathered from all sources was shared with the members of the network, and after an agreed embargo, with the wider community of the Eurovision News Exchange.

The story was broadcast by more than 50 TV channels belonging to 29 members, and there were many radio broadcasts and dozens of online articles citing the report.

It was the top story on February 14 in SR Sweden, RTVE Spain, and soon others picked it up, including outlets from outside the EBU community who were quoting and linking to the original report in members’ platforms, like Aftenbladet in Sweden or many websites in the Spanish-speaking world. There were even queries from Argentina.

None of it would have been possible without the exchange of views, information, cover plans, and the different elements of the story produced by each member.

Investigative journalism takes time, and investment, and it doesn’t always produce a smoking gun. But this time we got it right, and we got it first. Twenty hours after the publication of this report, the US State Department presented a study by the Conflict Observatory, from Yale University, confirming what the EBU community already knew at that point: that Russia is transporting hundreds of children from occupied Ukraine into Russia for foster care or adoption, including children who have families in Ukraine.

This practice can constitute a war crime, and when committed at a systematic level, a crime against humanity.

That will be for the courts to decide, but we can be proud that we as public service media did our part, which was telling this important story to our audiences.